ADRA

Adra is a small coastal town at the extreme southeren edge of Almeria Province. Just a mile or so along the coast is the border with Granada Province. The spectacular Alpujarra mountains rise up behind the town. Like most places in this part of Andalucia, Adra has a history going back for thousands of years. The old name, probably Carthaginian, for the town was Abdera. The name can still be seen around the town as it is on the Adra coat of arms. The Romans (naturally!) were here and there are Roman remains in the town. The biggest problem that the town had for centuries was attacks by pirates. It was completely sacked on several occasions and the inhabitants killed or taken for slaves. Incredibly there were still raids at the time the GSSR was being constructed.

Adra Industrial Archaeology

The Adra Port Line

Please note. The five pictures below, relating to the port line may be expanded by hovering the curser over them. They were used to develop my understanding of the clever piece of code by Scott Kimmler of randsco.com, who I acknowledge here, as well as my thanks to John Hearfield of johnhearfield.com for his help in evolving the code. The pictures heve been left in for interest - DG.

The port of Adra, left, was built between 1916 and 1920. To supply the hardcore for the project, a metre gauge line was built to a quarry (called Campanillo - little bell) on the outskirts of the town. For such a temporary line, a surprising amount remains.

Leaving the port, the line followed the Almería road. It followed the road for about a mile, then turned left into the quarry. Here it passed a weighbridge then entered the quarry.

It had two locomotives from the German company Orenstein and Koppel. They were 060 engines but what happened to them afterwards I do not know. I assume that ordinary open wagons were used but again I have no knowledge of them. This old picture shows an engine taking rock to the port. Compare it with the modern picture (b) below

The pictures show, (TR) The entrance to the cantera (quarry) from where the stone for the port was brought. On the left is the building that housed the weighbridge. The control signal is still there on the roof; (TL The engine shed, now used as a store. I was told by some workmen that there are still railway lines under the floor but cannot confirm this; (BR) The remains of the water tank for the steam engine; (BL) A View of the port today.

The Sugar Factory

Sugar is produced from two sources, sugar cane and sugar beet. In Spanish they are known as azucar de caña and azucar de remolacha. Whilst sugar cane makes sense in the southern Spanish climate, I was surprised to find that sugar beet, which is associated with mild, damp climates such as England and northern France, was also grown extensively. On p177 of my book on the GSSR I give a short description of sugar beet production, reproduced by kind permission of the British Sugar Beet Corporation.

British SugarSugar was first produced and exported from Adra in the 16th century to Genoa. Other factories were built but suffered from the pirate raids mentioned above.

In 1862 The Santa Julia refinery produced 6,000 arrobas (1 arroba = 25lbs, 11.34kg) and sent cane sugar to the Universal Exhibition in London. The International Exhibition of 1862, or Great London Exposition, was a world's fair. It was held from May 1 to November 1, 1862, beside the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society, South Kensington, London, England, on a site that now houses museums including the Natural History Museum and the Science Museum (London).

However, by the end of the century, despite at one stage employing over 100 people, the factory was abandoned. Some of its roof were used to repair the right wing of Inmaculada parish church in the town centre.

There were two other refineries, St Nicolás and St Luis.

St Luis was constructed at La Alquería a few km inland and St Nicolás in 1870 at the mouth of the Adra River. St Nicolás suffered from erosion problems when work on the river created a new course. In 1883, two workers were killed in an explosion. There was fierce competition between St Nicolás and St Luis and charges of espionage were levelled. The situation was not helped by the two owners holding different political views. In 1894 St Luis closed, leaving St Nicolás with no competition.

In 1898 the St Nicolás factory was sold to the large Larios Group. This was not a good move for the workers. There was continual unrest due to the poor wages and in 1901 there was a riot and the factory was burned down. (The sugar refinery along the coast at Motril in Granada Province, also owned by Larios suffered the same fate. The remains of this factory were only recently demolished).

A third factory of small importance was the refinery of Pago del Lugar. It lasted only from 1882 to 1884. The location, near to the river and sea, then went through a chequered career, owned by an English concern, then a factory for conserving vegetables, whose owner was assassinated in the Civil War, then seized by the Banco Español de Crédito. Today the area is being developed as a large housing estate.

AZUCARERA DE ADRA S.A. (The Adra Sugar works Ltd)

After the unrest, there was the danger of a total collapse of the sugar industry at Adra. However, after negotiations a cooperative was formed and an agreement was signed on May 16, 1909 in Madrid. The business was called initially "Our Lady of the Sea". The first sugar was processed a year later.

In 1922 it became a limited company. The installations were expanded and the machinery was installed for the mixed system of cane and sugar beet for the first time in Spain.During the next few years the company expanded, and underwent a number of management changes.In 1930 there were 34,497 metric tonnes of beet processed, a record. The beet came in part from the fertile plain of Adra and of the regions of Baza and Guadix. Unsurprisingly the Civil War played havoc with production, although it did continue. After the war, production was centred on cane rather than beet, although by the 1950s production was once more mixed.

By the middle 1950s there was a resurgence of the production, with 12,000 metric tonnes of cane and 14,000 metric tonnes of beet. Over the next ten years or so, the company tried a number of techniques for improving production. However, in 1969 the cost of transport made beet production uneconomic so only cane was processed. Production limped along for the next few years but in 1972 the factory closed and the equipment was taken to Badajoz.

The rusting plaque above showing the arms of Adra is on the wall of the old sugar factory.

Today the factory stands empty. There is (was?) a sign on the wall outside saying that the factory would become a heritage site but nothing much seems to have happened yet.

Update 2008. The factory has been renovated and is now an alcoholics rehabilitation centre. The rusting plaque has gone, where I do not know.

LEAD

Lead working, like the rest of Almería saw its biggest boom years in the latter half of the 19th century, tailing off as iron workings began to appear. Similarly it was foreign investment that dominated.

Adra was one of the earliest producers of silver and lead and its derivatives. It became the main port exporting these products from the nearby Sierras de Gádor and Almagrera.

The manufacturing of lead in Adra required a high degree of capitalisation and until 1839 it monopolised almost all the lead extracted in Spain. However, because of the quantity and quality produced, there was a drop in lead price, putting many concerns in jeopardy.

In the 19th century, lead had a huge quantity of products and economic sectors that depended on it. (pipes and roofs for the construction, lead oxide for making paints, shot towers for production of munitions, dyes and enamels, crystals, tanning, pottery, rubber manufacture and refining of copper and silver).

The lead factories of Adra (and elsewhere) benefited from the prohibition of crude ore exportation. This was the reason for the many lead mine factories in Almeria. There are a lot of remains still to be seen between Villaricos and San Juan de los Terreros.

But lead and its derivatives were products little demanded in Spain, except for the shot towers for the army and the material for the glazing of pottery. Because of this the manufacturers of Adra relied on ships that usually went to the French port of Marseilles. From here it was sent to the remainder of Europe and the world.

The lead and the silver economy had four distinct phases:

- From 1820 to 1829: The time of greatest production that coincided with the major raising of lead price in the world market.

- From 1830 to 1836: The price of lead falls under the avalanche of production from Almería and Adra. Production falls.

- From 1836 to 1840: Moderate recovery.

- From 1841 to 1850: Slow decline of the mines of the Sierra de Gádor, culminating by 1880. In this phase begins the great importance of cupellation (a shallow, porous container in which gold or silver can be refined or assayed by melting with a blast of hot air which oxidizes lead or other base metals) of silver by the discovery of galena silver bearing seams in the Sierra Almagrera.

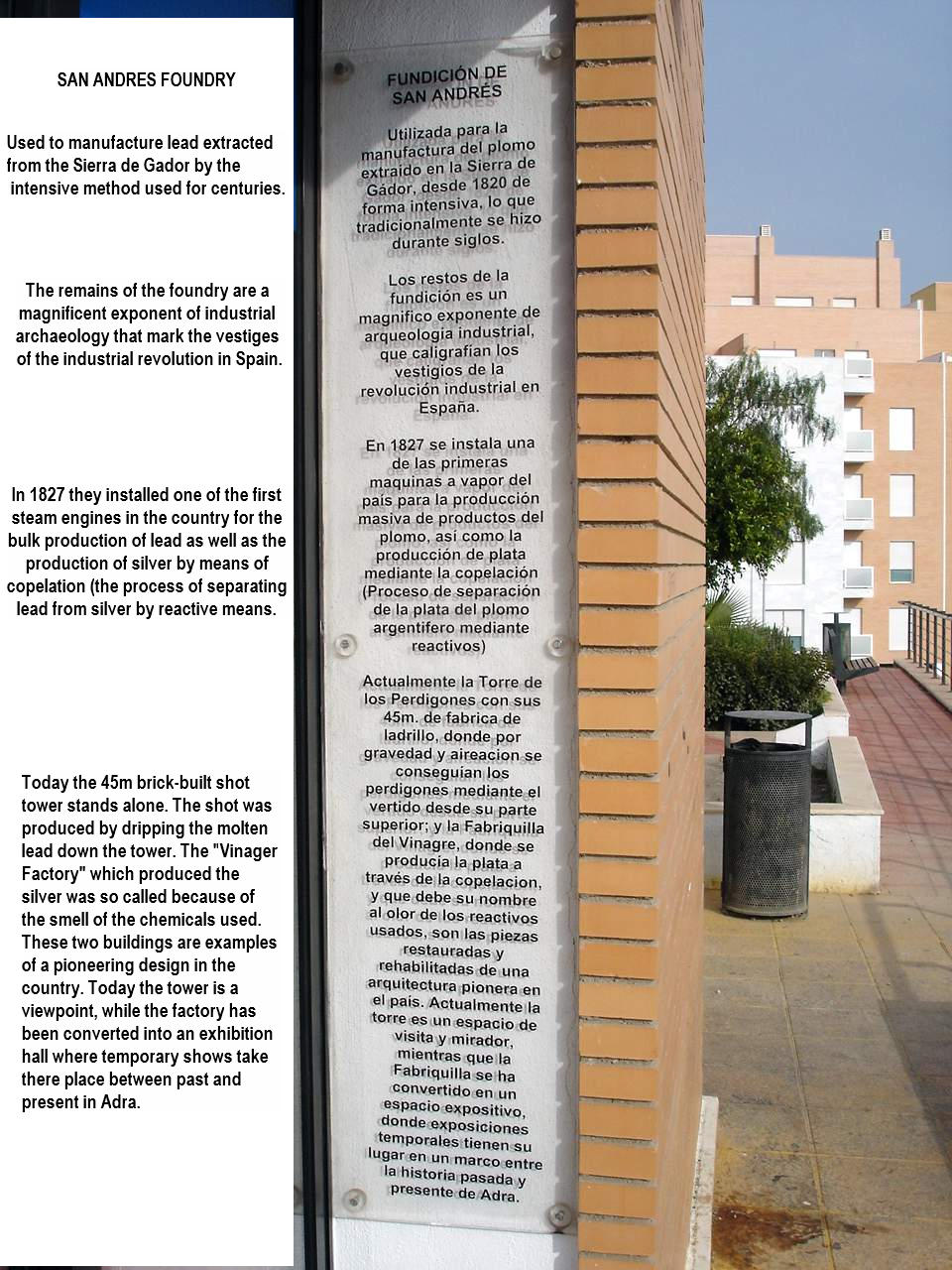

THE SAN ANDRÉS FOUNDRY: 80 years of activity

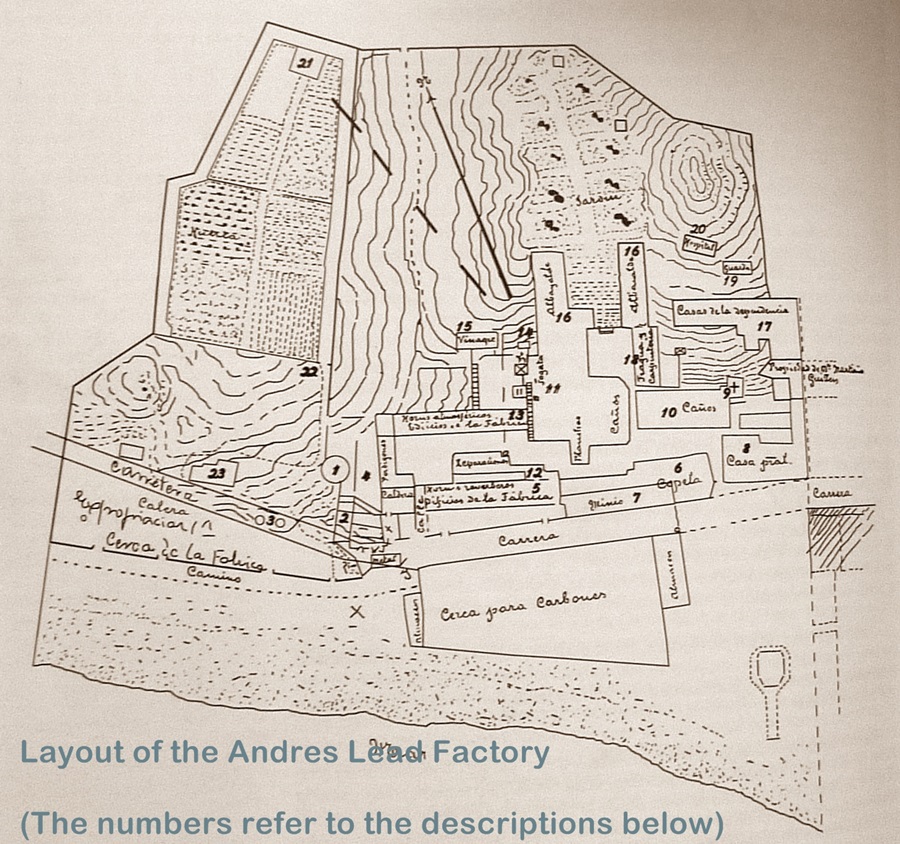

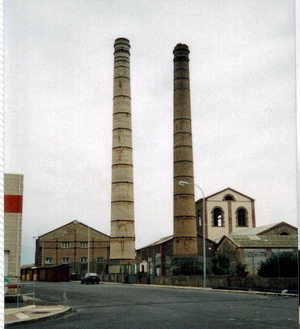

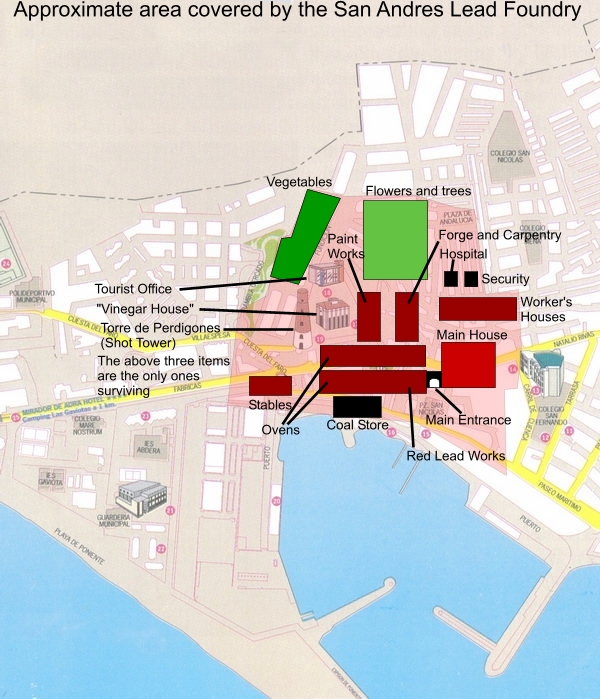

The top picture is a sketch showing the location of the main buldings of the San Andrés foundry. Below it is the balcony of the tourist office, with a translation of the information there.

On the left is the "Torre de los Perdigones" (the Shot Tower). Below is (L to R) a view to where the ovens stood, the same view from the opposite side showing the tower and the Vinager House and the only remaining tunnel into the ovens.

The San Andrés foundry, is linked to a series of innovative industrial innovations that marked the Adran economy from 1820 to the end of that century. It was conceived as a large factory following the English model of the time. The technology, technicians and even the coal came from Britain. In 1837 what is claimed to be the first steam engine in Spain was introduced. Up to the middle of the 19th century it was the most important producer of lead and silver in the country.

Like lead itself, San Andrés had four economic phases:

- In 1820-22 San Andrés is built and English coal burning ovens are installed.

- In 1837 three steam engines are installed.

- In 1840 activity is expanded to include the cupellation of silver from the mines of Almagrera.

- From 1850 San Andrés continually specializes in products that allows the factory to remain operating until 1880.

A Brief history of the works

San Andrés was built toward 1820 by the business Rein and Cía and soon became the leader in its field, benefiting by its proximity to the Sierra de Gádor and by the prohibition of mineral export. This firm operated mines in Asturias to supply the coal.

In 1822 they installed three reverberation ovens and two others but they gave poor results.

Joseph Rein, German of Saxon origin , (his family had lived in Málaga since the 18th century) decided to give a new technological impulse to this great foundry, and brings Welsh technicians to install six English coal fed in 1824. These ovens give such good results that four more are installed. The ovens give a 68% increase in production. He also overcame the prohibition of coal imports to Spain.

In 1825 the director of the company was a German, Federico Grund. This would not be particularly noteworthy were it not that he also was the British Vice-Consul in Adra. Presumably countries shared these duties.

By 1827 the company emloyed some 500 people. However, by 1827 the international price of lead had fallen considerably. The company was bought by Manuel Augustin Heredia, a Malagan merchant. He modernised the factory and widened the scope of its products. These products included pipes, plates, shot, pellets, white lead and paint.

Drop in demand and exhaustion of the lead mines led slowly to the factory finally closing at the beginning of the 20th century.

After closure, the administrators rented out some of the buildings. During the civil war, the republican military took over the site and mounted a machine gun on the shot tower. After the war, the roofs were stripped of lead and the buildings left to rot. Today, apart from some ruins, only the shot tower and the vinegar house remain.

A detailed look at the works

Hover over the plan to enlarge it. Make sure that the diagram is at the top of your screen before you do so.

Source Farua, History of Adra.

The Shot Tower (1)

This produced lead shot by dropping molten lead down the tower. Due to the height, the lead formed round pellets as it fell. Air passed through the lower sections to cool the pellets. It measures 44m in height, 7.5m diameter at the base and 4.45 at the top. Before a restoration in 1984, it had a spiral staircase. It has a concrete base with the main part of brick. At the top was an oven for heating the lead.

Update. Courtesy of Robert Vernon, attached is a picture looking down the tower. This now accessble by a new staircase.

Covered Way (2)

Down from the shot tower and the ovens, a covered way led down to the harbour. Raw materials came up from the harbour and finished products went down to it.

Lime Kiln (3)

Lime was always needed for building repairs. It was made near the covered way. Limestone was paced in layers with fuel such as wood or coke then heated for several days. This produced quicklime, a dangerou powder which here was used to make lime mortar for buildings. A curious link with lime was that in our early days my wife and I worked at Bedford telephone exchange which was situated in Lime Street, where many years ago there was a lime kiln.

Grading room (4)

Next to the shot tower was a building where the pellets were sorted, graded and finished.

Reverberation ovens (5)

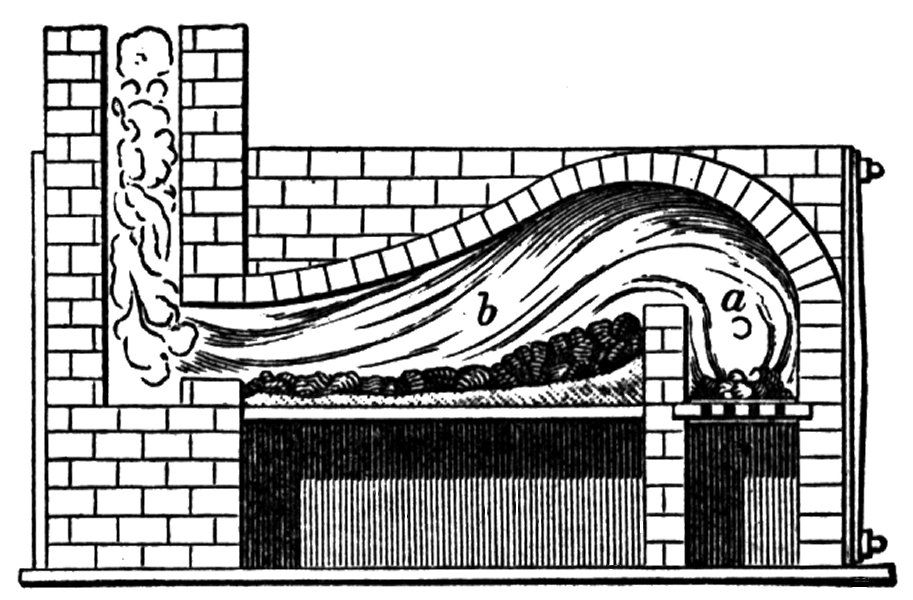

A reverberation oven is generally rectangular, that reflects (or it reverberates) the heat produced in an independent fire location see diagram. These were used to separate silver from galena and supplied hot air to the hearth. They were later replaced by more modern ovens of British design.

Hearths (6)

This is where the silver was obtained. They were one-off use and used bones in their construction.

Red lead (7)

Produced by reoxidation of lead, hence its proximity to the ovens. Used in paints although less so these days due to its toxicity.

Principal House (8)

The lower floor was for administration and the upper for the directors. Later a third floor was added. Now destroyed

Hermitage (9)

Services were held here on Sundays and special days.

Tubes and sheets (10)

This was a long building [25m], necessary for the fabrication of these items.

Bonfires (12)

Here they melted the lead for making into the tubes and sheets in building (10). Here they also calcined the bones for building (6)

Atmospheric ovens (13)

These were used on ore that was poor in lead or other minerals. I have been unable to find any pictures of ovens of the period.

Cistern to hold the sites water supply (14)

Vinegar House (15)

Originally the company office before (8) was built; it was then used for the production of vinegar and acetic acid. This was used to produce lead acetate, used in dyes and fixatives.

White Lead (16)

Used as a paint pigment, mostly banned now. In the middle ages, ladies used to paint their faces with it. The long term effect was lead poisoning.

Offices (17)

Forge and Carpentry (18)

Security (19)

Hospital (20)

Apart from dealing with the daily accidents, there was also a wing to deal with lead-related illness.

Reservoir (21)

This held water for the vegetable garden below it.

Gate (22)

It controlled access to the garden.

Stables (23)

For information on the town, go to this site. Adra Tourism

©Copyright Don Gaunt

Click here to go to the Faydon.com Home Page